David Howard has long been a playwright, but he is best known as the award-winning screenwriter of the science fiction comedy "Galaxy Quest."

David Howard has long been a playwright, but he is best known as the award-winning screenwriter of the science fiction comedy "Galaxy Quest."

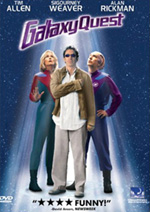

David Howard wrote the original story and co-wrote the screenplay for Galaxy Quest, the surprise hit science starring Tim Allen, Sigourney Weaver and Alan Rickman. "Galaxy Quest" grossed over $71 million at the U.S. box office.

David Howard received both the Nebula and the Hugo Awards for Best Dramatic Presentation. The Hugo and Nebula are the highest considered the highest awards in science fiction. In winning these awards, "Galaxy Quest" beat out competing nominees such as Being John Malkovich (Spike Jonze, Charlie Kaufman); The Iron Giant (Brad Bird, Ted Hughes); The Matrix (Andy and Larry Wachowski); and The Sixth Sense (M. Night Shyamalan).

Howard has become a frequent commentator on theater, screenwriting, and Latter-day Saint media, and has participated in multiple film festivals and symposia, such as the 2001 Vision Film Festival in Los Angeles (alongside Academy Award-winning director Jerry Molen and famed television producer Glen Larson).

Howard's other works include "The Fast", which made a successful five-week run at the Rose Theater in Venice, Calif.; "Electric Roses", published by Samuel French Books; and The "Rite of Spring", produced by Second Stage in southern California. He now lives in Santa Monica,

David Howard was born in Cedar City, Utah but grew up in Arizona. Howard graduated from SUU with a bachelor's degree in theatre. He is also the holder of an MFA degree from the University of Utah, and a master's degree in theatre from Penn State University.

[The following interview is from the filmforce website at:

http://filmforce.ign.com/articles/35850p1.html

It is been temporarily archived here while offline on that site.]

FilmForce - - Interview

Welcome to the first installment of Kenneth Plume's three part interview with Galaxy Quest screenwriter David Howard.

In Galaxy Quest, the cast of a defunct Star Trek-like television series is recruited by real aliens to crew a real starship, and fight a real interstellar war.

Many science fiction / television aficionados have heralded the film as one of the most insightful and heartfelt evaluations of SF fandom and television pop culture ever to hit the screen. The film level-headedly considers the dangers of believing in fictional icons (and losing one's identity inside a fantasy world) a little too much -- but does so in a way which neither alienates or offends the audience to which it speaks.

In his conversation with Ken, Mr. Howard (a playwright-turned-screenwriter) discusses his background, his philosophies about writing, the immense difficulties of breaking into "the business", and the circumstances leading to the conception and development of Galaxy Quest.

Be sure to check back with FilmForce over the next few days – as Ken's interview will run throughout the week.

PLUME: Tell me about your background...

HOWARD: I'm a playwright, actually. I'm one of those overnight sensations that have been at it for over 10 years, so I've really been writing for quite a while. I've had some success as a playwright -- I have a grad degree in playwriting from the University of Utah.

I've had a number of equity-waiver productions throughout that

time. I have a short play that was published in an anthology by Samuel French Books, called Electric

Roses. I moved out here [Los Angeles] 10 years ago to pursue screenwriting. That's pretty much when I made the transition to screenwriting -- and there are several other pieces that I wouldn't show anybody. But this is the first one that's been picked up and done.

PLUME: Were you originally from Utah?

HOWARD: Kind of. I was born in Utah, and grew up in Arizona -- but I've lived a number of other places. I did an internship when I was in my grad program at the Actor's Theatre in Louisville, Kentucky, and I went to school at Penn State for a while. I've kind of been around, mostly in the West, though.

PLUME: What drew you to playwriting, or writing in general? Is it something you've always done?

HOWARD: No, no it's not. When I started college I was a music major, and I went to a production of Godspell that just blew me away. After that, I really wanted to try acting, so I pursued a degree in acting through my undergrad work.

I was in a grad program – a professional acting program - when I was at Penn State. I realized I was more interested in what was being said than whether I got to say it. It also seemed like the more training I got, the more critical I got of my work -- so I became much more interested in being able to edit what was going out, and that's when I transferred into playwriting.

PLUME: As a playwright, how would you describe the transition going into screenwriting?

HOWARD: For me, it was much more difficult than I anticipated. One of my professors said that...when you look at a play...it's 75% verbal, and 25% visual. In a film, that's inverted. I think there's a lot of truth to that.

In plays...out of necessity...you have to deal with language and ideas, whereas converting ideas into visuals involves using a whole different part of your brain. There is a transition to be made there. So, I suppose I would encourage any writer to write a play, for a number of reasons. First of all, because it forces you to deal with ideas rather than just blowing things up, or creating special effects. I think any good film has to have some significant human idea at the heart of it.

Also, it's much easier to see and hear your work in the theatre. I belong to a writing group out here with some other screenwriters. One of the writers there...a fine writer who's made a very good living for himself...has never had an opportunity to hear his dialogue read. Ever. When I heard that, I was shocked. I thought, "Gosh. How hard is it to get your buddies, go in the garage, and put it on?" You know? I really think there's something to be learned just through the practical staging of a piece.

PLUME: Do you think visuals can be a crutch?

HOWARD: No, I wouldn't say that -- I would say it's a different

medium. Visuals can be every bit as powerful as

something verbal, but it's just a different way to

communicate.

PLUME: And it's best to work both of those muscles...

HOWARD: Definitely. Absolutely.

PLUME: What prompted your move to Hollywood? That's a major step to take...

HOWARD: I never saw myself exclusively as a playwright -- I always wanted to write film. Actually, I always wanted to do both. There are some ideas that seem to be better expressed as a play, and some that are better in film -- I always wanted to do both.

But...quite frankly...my father died a few years before I came out, and my mother was living in Utah by herself. Part of it [moving to L.A.] was because I was a coward and thought, "You know, for me, L.A. just seems a lot safer than New York." Maybe it was just naïve of me to think that -- but at that point, it just seemed like something I could deal with rather than having everybody in your face like they are in New York. Or you hear they are...

I don't want to badmouth New York. I've really enjoyed visiting there , but living there was something that was really intimidating to me -- and it was a lot further away from where my mother was living. I just thought, "You know, if I live in L.A., I can just hop in the car and drive home several times a year – whereas, if I'm all the way across the country, I've got to book a flight, and who knows how much that is going to cost. Blah blah blah blah blah."

So at that point it was just "Let's go to New York" or "Let's go to L.A." and L.A. just seemed like the better choice for me.

PLUME: What kind of expectations did you have in going out?

HOWARD: I had the same naive expectations of success that I think everybody has. I had a full-length play, and I had a screenplay ready to give to people when I got here. I found out that neither one was what anyone was interested in. It's taken me a number of years to get something that somebody else thought was worth sinking their money into.

PLUME: What procedure did you follow when you got to Hollywood?

HOWARD: One of the good things I had going for me was that I did an internship at this regional theater - The Actors Theater of Louisville, which is a real fine theater and they do a lot of original plays there – so I started doing my networking before I got here.

There were some people in my grad program who knew some people out here, so I started collecting names of people I could contact. I wrote all the letters before I came down saying, "I'm moving down, and I'd really like to speak with you." I had half-a-dozen meetings set up with people when I got into town. Nothing ever came of those beyond, "Hello. How are you?" I think that had I paid more attention at those meetings I could have saved myself a lot of time -- but you go in there with your scripts and you think / assume that someone is going to pick those up and say, "Great! Let's do this!" Which doesn't happen very often at all.

At the same time, it gave me a chance to hit the ground running. I did have opportunities to get jobs, both in production and in development. You know, the business side of things. That was really valuable to me, and the other thing I did is that I temped. The first job that I got at the Disney studio...so I was back in the back-lot from then on...and I met

people. I had a couple of doors open right then and I think that...had I known my craft better...I could have saved myself a lot of time had I been really ready when I got here. But I guess I really wasn't.

PLUME: How long ago was this?

HOWARD: Over 10 years ago.

PLUME: Give me an overview of the hardships faced by a screenwriter in Hollywood. What kind of hurdles are there?

HOWARD: Well, you know, it's funny when you look at how it works. The people who make decisions...there are maybe only 20 people who can really say, "Yeah, we're gonna make a movie"...but the people who can make those decisions are so bombarded with ideas that they naturally surround themselves with walls.

It seems to me that Los Angeles is a city filled with dreamers. They're here to be artists, but they're never going to be them. They're really here to be waiters -- and they just don't realize it. That's very sad, but for every one person who's here seriously to pursue a career as an artist... whether that's as an actor, or a writer, or a director...there are 99 other who want that but aren't willing to invest themselves in it.

The writers don't write, or they have one script...and a lot of dreams...and a lot of big ideas -- but they just can't do it for one reason or another. Whether it's ambition or, whatever. So, the difficulty is being recognized as one of the people who is not one of those people.

PLUME: So it's like being a small fish in a big pond with a lot of fish...

HOWARD: Yeah, and it's not even just a lot of fish. It's like a lot of fish that nobody wants to look at – a lot of ugly fish.

PLUME: A lot of fish that have been thrown back...

HOWARD: Exactly. So the real hard part is being noticed. It's having that perception changed...so that you are not one of those people...but you are serious, and you are talented, and you are someone who someone is willing to spend their money on -- that can come up with a project they are willing to invest in.

PLUME: In your mind, is there a roadmap? Or is it merely a set of circumstances that are specific to each person?

HOWARD: I think that there are lots of ways that you can get to where you're going -- ultimately everyone has to find their own way in. There are roads that are more commonly traveled, but I didn't take one of those roads. None of them guarantee success, but if you come down here when you're eighteen and you go to UCLA Film School, you will meet people. You can't help but meet people, and in that sense there's more of a chance that you can make the connections, and get yourself into a job and work your way up through the steps that people traditionally take.

My story is completely different from that. I moved here with a background in playwriting, and my film was made because I gave my script to a friend of mine...I had no agent and had no connections...and she said, "You know, I really like this. I think someone might be interested in doing this."

She partnered with another woman who works at Beacon Pictures, and they got it to CAA (Editor's Note: CAA = bigtime talent agency in Hollywood), and from there it went to the studio. So mine came in through...like...the total back door. I wouldn't advise anyone to try to do that, because that's like coming out here and expecting lightning to strike you. But at the same time, I knew that I had a really good story -- and I believed that my script was good. You have to do that, because nobody else will. You really have to believe that you have the talent and that you can work.

PLUME: Do you think it's almost like an obstacle course, or maze, that's required for a writer to go through?

HOWARD: Absolutely. I don't think it necessarily has to be that way, but it usually works out that way – a certain attrition takes place. Plus, I think there's a big difference between what's in your head when you're 19 – and when you're 29. I think that's one of the downsides to the whole ageism thing. I can only speak for myself -- I was a much more perceptive person when I was past my twenties, than when I was in my twenties.

PLUME: Do you believe that helped your writing?

HOWARD: Oh definitely, yeah. Now some people are just brilliant, or some people are just so tuned into the culture that they know "what people are going to want". But I'm not that hip. I'm the first to admit it.

PLUME: You're also a family man...

HOWARD: I am.

PLUME: Writers are frequently perceived as having a tough time getting by in the biz. How would you describe a writer's life -- knowing you have a family to support?

HOWARD: What I think is this. I made specific decisions that would facilitate my writing career. I chose to have a day job, because if I had had a job that I really had to apply myself to, I don't know that I ever would have had the energy to write when I got home. I think, realistically, if you can't have a day job...if you need a real job...then you better darn well know how to write before you take that job.

I think if you're really disciplined...and you're ready to make the sacrifice of all your free time...you can do that. You can get up at four in the morning and pound out a script. I think, though, that you don't have a lot of chances to keep doing that, because it takes too long to learn how to write -- it did for me anyway.

I think that the reason I was able to do what I did was because I'd gone to school. One of the reasons I'd gone to grad school is because I thought, "Okay, this will give me a couple of years. I could starve for a lot less money with a graduate stipend than I can driving a taxi cab." I could also be in a much more stimulating environment, and have places where my stuff could be read and workshopped.

And the day job really worked well for me. I worked for the sales department of this big corporation that sold phone systems. And, because it was sales, it was really spur of the moment kind of stuff. "We need this proposal typed up." I was a word processor -- but there were a lot of days where there was very little for me to do...and I should be embarrassed to say this...but I spent hours on the company time typing up screenplays. And they knew what I was up to, so I didn't feel too bad about it.

At one point, one of my bosses walked by and saw me typing away and just shook his head and said, "We should be charging you rent." That was a great situation, because I had a full-time job. I had to be there...that was my discipline...because I had to be at work. It was either write, or play solitaire on the computer -- and there's only so many hours you can do of that. So I would write...and I had great insurance...so I could take care of my

family. We weren't making a tremendous amount of money -- my wife was teaching in the evening...so I'd come home and she'd go to work...but we were able to do it. Fortunately, when I got married, my wife knew what I wanted to do, so it wasn't like I all of a sudden quit my job at the law firm and decided I wanted to be a writer.

PLUME: So she went in with her eyes open...

HOWARD: Yeah. And she really believed in me, which helped a lot.

PLUME: How would you describe your writing process?

HOWARD: It varies from project to project. Sometimes, I'll just get an idea that I think is really exciting -- and from there I just let it develop. For example, when I wrote my draft, Captain Starshine... which became Galaxy Quest...I got the idea when I was in an IMAX film. I was waiting for the film to start, and the trailers for the coming attractions started, and there was a feature coming called Americans In Space.

The voiceover for this trailer was Leonard Nimoy, and it took me a few minutes to recognize his voice. Then it just struck me, "Aw, that poor guy." I could just see these marketing guys putting this together saying, "Who could we get to do this?" "Oh, let's get William Shatner." "Oh no no, he's out of the country. Who else is there?" "Let's get Leonard Nimoy!" You know? The idea of being trapped in that world struck me as something potentially very funny. How do you walk away from that and decide, "No, I'm not going to do that anymore..."?

I just started playing with the idea of them being in this world, and all of a sudden real aliens show up. This was a script that...in a lot of ways...just wrote itself, because it just seemed so self-evident once the idea was there. So, in answer to your question: a lot of times something will just spark my interest and I'll think, "There's something there." There's something there that is intriguing on a human level, and I'll start exploring it, and the plot will come later.

PLUME: Do you find the process easy or agonizing? Or is it a mixture of both?

HOWARD: The answer to that is yes. It's really funny, because there are a lot of actors who can do things that I can't do, and there are a lot of really gifted directors - but I really believe that there is nothing more difficult than sitting down at an empty page, and creating something. In all the other fields, you have something to go on -- you have something to base your decisions on. But with writing, you're just completely alone and completely out there.

It can be so agonizing to start with something new. When you don't have word one done. What I like to do so I don't have to deal with that is... if I'm in the middle of a project, when you reach those places either where you don't know where to go or you're blocked in some way...I'll write a few scenes from another script. Just so when I go back to that blank sheet the next time, I'll have a sense of what I want to do with my next project.

There are also times when an idea gets really exciting to you, and I really think you need to take advantage of that excitement -- because that's what's going to carry you through all the tedium and problem-solving and all the other stuff you have to go through to get through a draft.

PLUME: Do you think the process snowballs as you get towards the finish?

HOWARD: I think that happens a lot. In this writing group that I go to...and I don't know where this comes from...but they talked about there being places where you hit a slump. There's like a 30 page slump. Anytime you start with a script, you have this idea that it's going to be brilliant, and you have to deal with the reality at page 30 that, "Maybe this isn't as brilliant as I thought." Then...around page 70 or so...there's another lull where you're fairly close to being done -- but there's still that whole other act that you've got to write, and the second act is always so problematic anyway. All the reality of what you have to deal with kind of hits you.

PLUME: Don't you think those are the natural breathers in the course of a story anyway?

HOWARD: Yeah, I think those are natural. And, of course, every project has its own idiosyncrasies. And there are certain problems that are going to be inherent in any story that you have to get over.

PLUME: Are there scripts where you reach a certain point and decide, "I can't pursue this any further..."?

HOWARD: I do that. If you're writing for yourself...and you're not being employed to write...you can do that. I think that can be really healthy -- because sometimes things have to gestate or ferment for a while, so step away from it. The great thing about writing...as opposed to being a dancer or something...is that if you put it in your files for six months, it's going to be the same thing when you take it out. It's not like you've lost your turn out, and a lot of times you'll have the answer that you need when you come back to it. In any case, you'll probably be able to see it more clearly.

PLUME: As opposed to being say a director, who has a budget and a schedule, a writer has the luxury of time...

HOWARD: Right, and I think that if it's your baby...your spec...and you're not under the gun for someone else, I don't think you should feel guilty at all. It's amazing how much time they spend just sitting around puzzling things out. It's such a guilt-ridden process. You just sit there for hours and feel bad that you're not writing, when you really are working. You've got to give yourself a little bit of a break.

PLUME: Do you believe that being in a writing group is a healthy process?

HOWARD: Absolutely -- I really do, because writing is so isolating by its nature.

PLUME: But writers also tend to be very secretive...

HOWARD: You have to be careful. I guess I would say that there are I couple of guidelines I would go through in terms of forming a writing group. First of all, I would work with a group of people that I could trust. How do you find that? I'm not sure. The groups that I've been involved with, a lot of them have been theater groups-- and that tends to be maybe a safer place, because anyone who's writing for the theater isn't doing it for the money.

PLUME: The sharks aren't circling...

HOWARD: Exactly. The other thing that I would advise any beginning writer to do would be to work with the absolute best people that you can. You can spend years listening to the opinions of people who really don't know what they're talking about. I have been in situations where...and it's not that I'm the most brilliant person around...but I just knew that I was bringing more to the table than most of the other people there. Like in plays that were being produced -- if I could see the flaws in the design, that meant that the designers I was working with were not very good, because I'm not a designer. When I was solving all these other problems, that kind of tipped me off to the fact that I should be working with other people.

I guess this sounds pretty self-serving, but I think there's a basic selfish truth here that if you work with really good people, you will learn. And if you work with people that you're constantly having to lift up, you'll spend so much energy mired down in solving problems that you shouldn't have to solve. You

should be moving on and really learning from the people who really know their craft, so work with the best people that you can.

PLUME: Do you think Hollywood conforms to the stockbroker quandary that if they know so much about stocks, why are they working?

HOWARD: I think things in Hollywood have changed a lot in the last 20 years. I have a good friend who's a consultant...and he's worked with one of the studios...and the way he explained it was this, "The people who make the decisions now are not artists. They're businessmen. They understand demographics and they understand marketing and that sort of thing, but there are a lot of them who really want to make choices that they can justify in case something goes bad. And if you have a track record, then they're off the hook. 'Oh, well he wrote Jurassic Park. So what if he couldn't write? He wrote Jurassic Park, so that's why I hired him.'" I think there are people...and I'm not talking specifically about anyone...but I think there's a business mentality where art is not part of the equation as much as it was. A lot of people will admit, "I don't know what's good, but I know demographics and I know what sold before."

PLUME: They know how much a camera costs but not how to use it...

HOWARD: Yeah.

PLUME: And it's a Catch-22 for a struggling writer in Hollywood -- because they will only hire someone with a track record, but you can't get a track record if no one hires you...

HOWARD: That's so true. You really do have to make your own way, and there are so many ways to do that -- whether that's going to be to produce your own film, or make your own deal. You've got to get over this mountain. How am I going to go? I'm going to go up. You pick your own route and play to your strengths.

I am not a real schmoozy guy. I like to meet people and I like to have conversations with them, but I just feel so uncomfortable if I go to a Hollywood party. I'll meet...like...one person, and I'll want to leave -- it's just not my scene. Some people can work a room, and they can get jobs and all kinds of things, but I'm just not really like that. So I just write, and the one thing I can say for myself is that I wrote and wrote and wrote and wrote, and I've got a trunk full of stuff. I wouldn't necessarily show it to anybody, but I got better with each script.

PLUME: How surprised were you by the "Captain Starshine" sale?

HOWARD: I still don't believe it, frankly. It's like a dream come true. One of the most shocking things was...when I went on the lot where they were filming it, and they were using five soundstages... they had the Galaxy Quest cantina -- where they were making meals for the crew. I'm looking at these things and thinking, "Let's see, this started when I was temping...when I was in my little cubicle typing away...and all of this came from that." It's mind-blowing.

PLUME: What was your part in the acquisition process? Very often, you hear of a writer who's pushed aside as soon as a script is sold...

HOWARD: Well, that happens. If you're going to write for Hollywood, you've got to expect that on some level, because it goes into other people's hands.

It's really funny -- they did a promotional documentary thing for Galaxy Quest that they showed on the Sci-Fi Channel, which was really funny. It's kind of this Galaxy Quest retrospective, where they interviewed the cast members in this mock documentary. They were saying, "20 years after the series has been cancelled, they're back to make this new movie." It was really funny, and when I saw it, the producers of the film...Mark Johnson and Charles Newirth...played these "experts" on Galaxy Quest and talked about it as a phenomenon.

I got something out of that that I had never really seen before -- because I'm not a producer, but I could see how they had lived with this thing for so long. Once they start producing, it's theirs and they make all the decisions. I guess it's understandable that the writers...at some point...are just not part of the process anymore. Which is very different from the theater, where you're on the top of the triangle. If you don't like it when it's done you just say, "No. We're not going to do this." You could do that.

Even beyond that, there's so many things that get added to a script... in the design, in the direction, in the actor's choices...if you're not comfortable with that - you probably should be writing novels, where you do have all the control. Film is a very collaborative art form, and you just have to get used to it.

PLUME: Were you involved in the re-write process?

HOWARD: Yes and no. I was there briefly in the beginning, and I worked with them for a few weeks and submitted some ideas -- some of which did get fleshed out and ended up in the final script. But a lot of it is Robert Gordon's work too -- I think he did a terrific job.

PLUME: How has the film changed since its initial draft?

HOWARD: The easiest way to answer that is just by saying: it's the same guy's journey. My script followed just the captain much more closely, whereas focusing on the rest of the crew -- a lot of that was Robert Gordon.

PLUME: In writing the film, did you see it as an homage to "Star Trek"?

HOWARD: Oh yeah. People ask me if I'm a Trekkie, and I would say that I'm a "Trekkie once removed". I love Star Trek, and I really loved The Next Generation. I had buddy who wanted to write an episode of it once, and we wrote this episode together that never went anywhere -- but I got really hooked on it.

Right after I got married, I started watching it for research. It was on five days a week in syndication, so all of a sudden I've got this Star Trek habit...watching it every night...and my wife's going, "Who's this guy? What's happened to my husband?" It's really intended to be an homage. It's kidding, but it's kidding with respect -- and that's a tone in my draft that was maintained throughout.

PLUME: Many also see it as an attempt to do "Star Trek" better. Was that intentional, or was it just happenstance?

HOWARD: I don't think there was ever a competitive element. It's very interesting to hear people say that, but I don't think it was deliberate. I don't think there was a one-upsmanship kind of a thing going on.

PLUME: In the writing process, did you have any actors in mind for certain characters?

HOWARD: I can't say I specifically had William Shatner's cadences in my head or in my dialogue, but the plight of Captain Kirk and William Shatner...and his situation...was certainly in the back of my head. Once the script was done, I guess they approached Kevin Kline to do it, and he was my first choice. But I was thrilled with what Tim Allen did with it.

PLUME: Did your view of Tim Allen change once he was cast?

HOWARD: It's not that I had any preconceived notions about it -- I just didn't know his work all that well. I had seen The Santa Clause...which I really liked...but I wasn't a follower of Home Improvement. Frankly, I don't think I've ever watched a whole episode of the show. But, I rented The Santa Clause after I heard the he was going to be cast, and I was very pleasantly surprised -- because all I had seen were bits and pieces of Home Improvement. I thought he brought a real humanity to it. I also think they did a really wonderful job with the rest of the casting. The cast, in general, was so strong -- they brought so much dimension to all the characters.

PLUME: And there have been comparisons as to which characters may or may not represent certain well-know genre actors and their respective plights...

HOWARD: I feel almost guilty about the success of this, because it was just all waiting to happen. It's like finding a perfect artifact in the ground. You just find it. It's not like you made it. So many of the jokes were so natural that it just kind of happened.

PLUME: I've heard that the film ["Galaxy Quest"]... even as photographed... had sequences that were harder edged and more intense than what we saw in theaters -- but these scenes were cut out to make it less serious...

HOWARD: That's true. I understand there were two factions: one that wanted to make it more edgy and hip, and another -- who wanted to make it more family friendly, and I don't mean that in a pejorative sense. I really think they made the right choice, because I think it's sophisticated enough so that adults enjoy it on a different level than other people do.

But they did make a deliberate choice to tone some of the violence down and take some of the language out. If you watch closely, you can sometimes see where their lips don't exactly say what words come out.

PLUME: There is a view of DreamWorks as a very hands company [creatively]. How would you describe the process of working a project through them?

HOWARD: I really didn't work all that much with them. I worked with Mark Johnson Productions -- with their people. Those are the people that I worked with. There was one executive at DreamWorks... his name is Adam Goodman... and I know he was quite involved in it, and worked closely with the film.

It was my understanding that Harold Ramis was on to direct the film, but they had differences over casting. Harold Ramis wanted to use Alec Baldwin in the lead, but the DreamWorks people thought that Tim Allen was a smarter choice commercially, and Harold Ramis decided that... if he couldn't use Alec Baldwin... he was going to move on. At that point, I know that it was really a lot of Adam

Goodman's doing that it didn't just stall -- that it kept going. So DreamWorks was quite involved in it.

PLUME: Were you surprised by the success of the film?

HOWARD: I was surprised. It was really interesting, because... when I went to the premiere... I hadn't seen it up until that point. I had heard that at preview screenings that it was still in that kind of netherworld between something hip and edgy and something family friendly -- and that it was neither fish nor fowl. That it wasn't either one, so it wasn't very satisfying on either level.

However, I was just thrilled when I saw it. I thought it was hysterical. I thought, "This could really be big." But what really surprised me was the way that it was perceived after it opened. My wife and I decided to have a little screening of our own over Christmas, so we rented a little theater and invited all of our friends and family to come. After the screening, her friends came up to me and... almost to a person... said, "This isn't the sort of movie I would usually go to, but I really liked it -- and I'm not just saying that because you're Bonnie's husband."

Looking back, I think that was really telling. I think the film would have opened bigger had audiences known what it was. I think they thought it was a lot spoofier... and a lot more sci-fi specific... than the film turned out to be. Anyway, I think that's kind of how perceptions developed.

PLUME: Very much a word-of-mouth picture...

HOWARD: Yeah. And, I think the fact that there were a lot of non-Trekkies who went and enjoyed it was pretty significant -- but it did take word-of-mouth to get around. I think they marketed it to a very specific audience, but it had a wider appeal than that.

PLUME: How would you handle a follow-up? Lampoon other types of sci-fi? How could you pick up with these characters?

HOWARD: Oh gosh. I don't want to give any secrets. I do have some musings about it... and I think it would be really fun... but I think you would want to keep a similar tone.

PLUME: Do you think a sequel would fall into the "Scream" trap of being derivative photocopies?

HOWARD: I have a tremendous amount of respect for the way Mark Johnson and his people did it, because they made specific choices to stay away from that. When I wrote my script, it was really important to me that it not become Spaceballs -- that there be some real human investment in it, and that they... even as satirical as it was... have a life of their own.

The characters were real enough so that you cared about them, and that they had real transitions in their lives. If I were going to write a sequel, I would want to stay true to that. I think one of the strengths of the Star Trek series

is that they've done that. It's almost funny, because... what... the even ones are good, and the odd ones are bad? It's because they have to tear the world apart in one of them -- and then they have to put it all back together in the next one.

PLUME: Do you think it's easier to tear the world apart than to put it back together?

HOWARD: Well, it's certainly more interesting. I think that one of the fun things that they have been successful with in the Star Trek series is that the characters have progressed. I think you would have to do that if you were going to do a sequel to Galaxy Quest, and do it successfully. You have to take the next step, obviously.

PLUME: What do you think of "Star Trek" today? Many people are pointing to "Galaxy Quest" and saying, "That's what the Trek franchise should be."

HOWARD: I've kind of lost touch with that, I'd have to say. I never really followed Voyager. I gave it a shot, but it just never caught me. I think the reason that Star Trek has had trouble is that it's gotten away from what it was -- "to boldly go where no one has gone before." I do have to say that I'm speaking from not really seeing it, because I haven't really followed it. But you look at the series that have been most successful, they're the same thing -- the Enterprise and the Enterprise going out there and discovering things.

I really thought that the last couple of years of The Next Generation were really very good. I think, on one level, that Star Trek has got kind of a bad rap, and I think that's unfortunate -- because I thought they examined some really interesting, really significant human questions.

PLUME: Were you surprised when the comparisons began occurring?

HOWARD: No, no -- everyone knows what it came from. There was no question. If you can't see that, then there's no hope for you. It's so obvious! Come on...

PLUME: How did selling that one script change your career?

HOWARD: Night and day.

PLUME: Is it like you're suddenly on the map?

HOWARD: Oh yeah. Because it's so difficult to get anything sold -- let alone made here. There are so many people out here... and so many scripts floating around... and there are a lot of successful writers who never even see their work done. I've got a terrific agent, and in the last six or seven months, I've met more people who hire writers... and who develop stories... than in the previous 10 years. I was able to quit my day job, and now I write. I go to my little office, and I feel like I've died and gone to heaven.

PLUME: How many projects would you say you have in the hopper right now?

HOWARD: Well, I never have a shortage of ideas. It depends on how you want to define "projects in the hopper." I've met with about 30 companies. From several of those, I've had offers to look at material -- and see if there's something that'd I'd be willing to do. And, if so, is what I present to them what they really want?

Then I have a couple of things where I think I'm fairly close to something happening. I know that my next spec -- people are going to look at. I have the benefit of the doubt now. The same thing that kept me out... that keeps everybody out... is going to keep me in, which is really cool. But there's always the terror of the sophomore slump that's in the back of my mind.

PLUME: It's hard to define a sophomore slump if you have, let's say, 3 or 4 projects that have already been optioned...

HOWARD: Right. Right. That's true -- that's why you want to do the shotgun thing. As long as one of them hits, you're okay. If I didn't come up with another idea, I'm sure I could write for 10 years on what I've got in my head.

I have to say that one of the most irksome things that I experienced is when people come up to me... and they find out that you're a writer... and they say, "Oh! You know, I've got this great story. Why don't you turn it into a script for me?" I think, "No. Why don't you turn it into a script. I have plenty of ideas that I want to turn into scripts."

PLUME: And how often does that happen?

HOWARD: Regularly.

PLUME: More so now that you've actually sold a script?

HOWARD: Well, it's not like being a movie star. It's not like people spot you in the street and go, "Oh! There goes Sylvester Stallone!" You maintain your anonymity, which is something that I'm very pleased with.

I've gotta tell you that one of the most satisfying experiences as a writer that I've had was last Thanksgiving. We had dinner with some extended family of my wife's, and they didn't know me. We were sitting around the table, and they all said, "What do you do?" And I said, "I'm a writer." The question that inevitably follows that up is, "Would I know anything that you've written?" Up to this point, it's always been, "Well, I have a little play that was published..." or, "I'm working in a quirky little regional theater."

Usually it's, "No." But for once I could say, "You will."

PLUME: Do you think other writers look in awe at anyone who's sold?

HOWARD: Having been on both sides, yes. Before I joined this writing group, I knew several of the people in it. I remember going to a wedding, and one of the writers there... who was quite successful... was sitting at a table and it was like, "Oh, I've got to go talk to Jack Olsen! He's the guy who sells these things." There was something kind of magical about him that was very attractive. I went to a Christmas party not too long ago and it was very different, because...

PLUME: Now you were that guy.

HOWARD: Yeah. And you know how it is at parties, where you can hear people talking. I would be talking to somebody who I knew... and it was an industry thing, kind of a schmoozy party... and there was a group about 8 feet from us and all of a sudden they stopped talking and stared at us. It was obvious what was happening. It was very funny.

PLUME: It must be interesting to be on that side of the fence.

HOWARD: It is. It is. It's kind of strange. It's like being the homecoming queen. You're not being looked up to because you're anything special, but just because of the way you look. You know what I mean?

PLUME: It's all perception...

HOWARD: It's all perception -- exactly.

PLUME: Even though you did make that sale...

HOWARD: And I did write that script. But does that mean I'm a better human being? No.

PLUME: Well to them, maybe...

HOWARD: Sure.

PLUME: Where do you see yourself in 5 years? Is writing what you want to stick with?

HOWARD: I would like to do other things. I think I would like to direct at some point, but I'm not in a hurry to do that. Also, I have little kids, and I have no desire to not see them for a year or two years -- so writing is a really good choice for me right now.

Galaxy Quest was a commercial piece. I wrote that to sell that, and I was very willing to say, "Okay, you take that and do whatever you want with it. I'll take what I can get out of it. I'll take a nice check... and I'll take the

credibility that I can get... and if you want to put a talking horse in it, fine. You just do that." Which is not to say I'm not pleased that they didn't put a talking horse in it -- but there are stories that are more personal to me, that I would like to be involved in producing and making some of those decisions down the way. So I would like to do that.

PLUME: When it comes to getting that kind of control, do you think that selling a project gives you a bit more of the clout needed to do that?

HOWARD: Absolutely -- it's all perception, but the difficulty is that you've got to deliver. Once they give you the credibility you have to make something of it, which is another reason I think that writers should continually practice your craft.

Again, I think the theater is really good for that, or make short films, or shoot video. Just keep perfecting your trade -- because once you have opportunities, you really need to be able to take advantage of them.