|

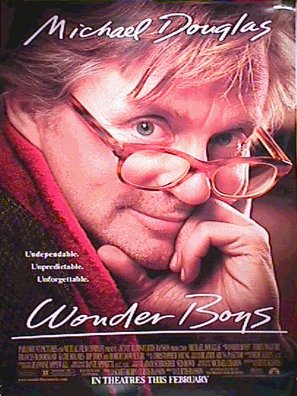

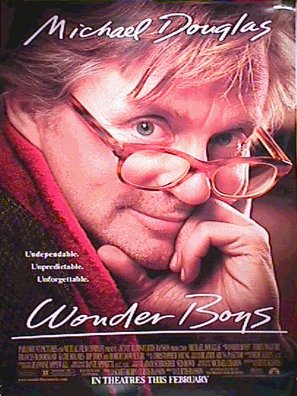

The movie "Wonder Boys" is a dramatic comedy based on the same-titled novel by Michael Chabon. The movie stars Academy Award-winner Michael Douglas as "Grady Tripp," a creative writing instructor at a small liberal arts college in Pennsylvania. Grady rents a room to one of his students, a Latter-day Saint writing student from Utah. This student - Hannah Green (played by Katie Holmes) -- is a talented writer and perceptive reader. She has already had two short stories published. Holmes is the fifth-billed actor in "Wonder Boys": the final member of the story's five principle characters.

"Wonder Boys" received an Academy Award for Best Song (going to Bob Dylan for "Things Have Changed"), and received Academy Award nominations for Best Editing and Best Adapted Screenplay.

The story in "Wonder Boys" begins with the protagonist stuck in a deep slump in his once-promising writing career. Seven years earlier Grady received national acclaim and the prestigious PEN Award for debut novel. His second novel The Arsonist's Daughter was mildly successful. But he has published nothing since. He has spent these years working on his next book, Wonder Boys. (Yes, main character Grady Tripp's unpublished novel has the same title as Chabon's novel, in which this story is told. This is just one of the things that the title of Chabon's book refers to - the "novel within the novel.")

The film begins on the day that Grady's wife has left him. To make matters worse, Grady's bisexual book editor Terry Crabtree (played by Robert Downey Jr.) comes to town from New York City and wants to see the book. Grady knows that his book is nowhere near being ready to let his editor see it. Early in the film it appears that Grady may have been suffering from writer's block, and that he hasn't written anything. It is revealed later on that actually his novel has grown to more than 2,000 single-spaced pages. His problem is not writer's block, it's that he can't stop writing, and he is leaving no thought, no detail out of the book. Grady's new book retains the superb writing style that garnered praise in the past, and individual parts of Grady's unfinished book are well-written, and the work is completely un-publishable.

Michael Chabon's book describes Hannah Green as a talented student from Provo, Utah, from a family with nine older brothers. Hannah love's her writing instructor's past writing. Toward the end of the novel and film, Hannah reads Grady's unfinished opus. She is able to give Grady some valuable insight about what is wrong with the book, and what is wrong with his life.

The novel explicitly identifies Hannah Green as a Latter-day Saint on page 113:

I'd never seen Hannah acting anything other than the calm, optimistic Mormon girl she was, eternally polite, capable of stolid acceptance of locusts, misfortune, and outlandish news about the universe.The screenplay adaptation by Steven Kloves includes two explicit references to Hannah's religious affiliation.

The first overt Latter-day Saint reference in the screenplay is spoken by Grady to his talented but troubled student James Leer (played by Tobey Maguire). Grady tells James: "She likes old movies like I do, that's all. Besides, she doesn't really know me. She thinks she does, but she doesn't. Maybe it's because she's Mormon and I'm Catholic."

Below is the scene from the screenplay (a revised version dated January 21, 1999) in which Michael Douglas' character Grady Tripp mentions that Hannah Green is a Latter-day Saint:

James nods toward the house, where Hannah Green can be

seen in a window, still fending off the determined Q.

JAMES LEER (cont'd)

...but the other night, Hannah and I were

together, at the movies, and she asked me.

Since she was coming. So I ended up coming.

Too.

GRADY nods, ponders this over-elaborate explanation.

GRADY

Are you and Hannah seeing each other, James ?

JAMES LEER

No! What gave you that idea?

GRADY

Relax, James. I'm not her father. I just rent

her a room.

JAMES LEER

She likes old movies like I do, that's all.

(glancing back at the window)

Besides, she doesn't really know me. She

thinks she does, but she doesn't. Maybe it's

because she's Mormon and I'm Catholic.

GRADY

Maybe it's because she's beautiful and she

knows it and try as she might to not let that

screw her up, it's inevitable that it will in

some way.

James looks away from the window, at Grady.

Below is the scene description as it appears in the screenplay. The character "Q" mentioned in these scenes is a wealth and successful best-selling author, visiting this college town for the annual writers event. "Q" was played by actor Rip Torn in the movie.

28 INT. HI-HAT CLUB Hannah Green is dancing with a sweat-drenched Q as GRADY enters this SMOKE-FILLED RHYTHM AND BLUES club. She beckons with a finger, but Grady--Nervous at the sight of her glistening Mormon skin--merely pantomimes an exaggerated shrug and she points.

The scene in the pub when Grady sees Hannah dancing is indeed in the final version of the film. Whether or not her skin appears to be "glistening Mormon skin" will have to be something each viewer decides.

The spoken line which overtly identifies Hannah as a Latter-day Saint has been cut from the final released version of the movie, however. This means that the movie does not actually contain explicit audio identification of this character as a Latter-day Saint.

Some clues remain in the film, however, revealing her religious background. In once scene, Grady and his editor (Michael Douglas and Robert Downey Jr.) borrow Hannah's car to go look for the car Grady had been using (loaned to him by an associate who owed him money). They wanted to find the car a valuable jacket (worn by Marilyn Monroe on her wedding day) is inside the glove compartment.

Although this film takes place in Pennsylvania, where much of it was filmed, the front and back license plates can be clearly seen in a number of scenes to be Utah license plates.

More subtly, Hannah offers Grady some pointed Word of Wisdom advice.

Hannah is a very positively portrayed character in the movie. Of the five principle characters, she is the least messed up. She seems like a fairly normal, intelligent, well-balanced person. She may not, however, be a perfect icon of Latter-day Saint virtue. About the copy of his book she received from Grady, she tells him, "And I love the inscription you wrote to me. Only I'm not quite the downy innocent you think I am."

Also, there are a couple of scenes in which Hannah openly flirts with her professor. Grady has many flaws, not the least of which is his philandering with the chancellor of his university (who happens to be married to the dean of his department). But at least with regards to his students, he basically tries to be a responsible, ethical individual (by secular standards). Grady does nothing to lead Hannah on and he does not yield in any way to Hannah's invitation to enter into a physically romantic relationship.

Below is the dialogue from the scene where Grady borrow's Hannah's car, as it can be heard in the final release version of the film. This scene leads to the scenes in which the Utah license plate on Hannah's car can be seen. It is when Grady borrows Hannah's keys that she offers him advice about his writing and his drug use.

[Grady and Terry are standing outside Grady's home, in the rain.]

Terry Crabtree (Robert Downey Jr.): So, what do we do now?

Grady Tripp (Michael Douglas): Find the jacket!

Terry (Robert Downey Jr.): Exactly how do we do that?

Grady (Michael Douglas): I've got an idea where it is. We could ask Hannah if we could borrow her car.

[New scene: Inside Hannah's room, the room she has been renting from Grady and Grady's wife. It was only as the film begins that Grady's wife left him. Hannah had not rented the room from a professor who lives alone. It is early morning. Hannah is still in bed. As the scene begins, Hannah is already sitting upright in her bed, wide awake. Either she rose quickly, or she had already been lying awake in bed - perhaps reading - when Grady knocked on her door.]

Hannah Green (Katie Holmes): Sure. Keys are on the desk, next to your book.

[Grady looks at Hannah's desk, on which he sees the three boxes which contain the typewritten only draft of his book. He had never told Hannah that she could read the book. Grady gives Hannah a slightly disapproving look, but he is more bemused than upset.]

[Hannah looks sheepish, and tries to explain.]

Hannah (Katie Holmes): I didn't finish it. Fell asleep.

Grady (Michael Douglas): Oh, it's that good, huh?

Hannah (Katie Holmes): It's not that. It's just--

Grady (Michael Douglas): It's just... what?

[Hannah says nothing. Grady does not say anything either, but he does looks at her for a moment and then sits down in a chair, waiting to hear what she thinks.]

[Hannah closes her eyes, considering whether or not she actually wants to tell Grady what she thinks. It would be easier if Grady would just leave. But clearly he is waiting to hear more.]

Hannah (Katie Holmes): Grady, you know how in class how you're always telling us that writers make choices.

Grady (Michael Douglas): Yeah.

Hannah (Katie Holmes): And even though your book is really beautiful, I mean, amazingly beautiful, it's-- It's, at times, it's, uh-- Very detailed. Uh-- You know, with the genealogies of everyone's horses and the dental records and so on and-- And I could be wrong, but it just, it sort of reads in places like-- You didn't really make any choices. At all. And I was just wondering if it might not be different if-- if when you wrote, you weren't always... under the influence.

[Grady clears his throat and then politely but firmly defends himself and his drug use.]

Grady (Michael Douglas): Well, uh, thank you for the thought. But shocking as it may sound I am not the first writer to seep a little weed. Furthermore, it might surprise you to know that one book I wrote as you say "under the influence" just happened to win a little something called the PEN Award... which, by the way, I accepted under the influence.

Grady (Michael Douglas): With Hannah's car keys and the boxes containing his manuscript, he exits her room.

Although Grady's comments to Hannah in this scene may seem like a rebuke, later in the day Grady gets rid of treasured stash of expensive, high-quality illegal drugs, which he had been using throughout the film. The final scene of the movie shows him considerably cleaned up, and clearly happier and clear-headed. In a voice-over he states that he gave up drugs completely, he got a fresh start on life, and he was able to start writing successfully again: something he had not done during the previous seven years.

Obviously Hannah has exhibited questionable behavior by flirting with her instructor. It is impossible to tell from the film the extent to which she would have allowed her professor "get to know her" romantically. But the dialogue and performance of the actress seems to indicate she was quite enamored with this professor whose writing she so admired, and she may not have been contemplating Gospel standards when she made her availability known.

Still, her overall appearance, intelligence, speech patterns and manner make it easy to believe that Hannah Green is a Latter-day Saint, albeit a probably imperfect one. The elimination of a key line of dialogue has not entirely excised the intentions of the original author and screenwriter. Probably the director filmed Hannah's scenes with the thought that she is a Latter-day Saint. The Utah license plate is not an accident. Hannah not only adheres to the Word of Wisdom throughout a film otherwise filled with drug, alcohol and tobacco use by other characters - she even offers her much-admired professor advice based on her knowledge and values.

[In the passages below, as through all the novel, the narrator is lead character "Grady Tripp," played in the movie by Michael Douglas. This excerpt begins while Grady is outside a party held during a writer's retreat at the college at which he teaches. He has just run into one of his students, James Leer: (played by Tobey Maguire). James mentions Hannah Green (played by Katie Holmes). This is the novel's first reference to the Hannah Green. At this point it has not yet been revealed that Hannah is a Latter-day Saint. These passages also mention Grady's literary agent Crabtree (played by Robert Downey Jr.)]

Pg. 47-50:

"I'm not supposed to be here, in case you were wondering," he said. He shifted his shoulders under the weight of the knapsack he carried, and looked me in the eye for the first time. James Leer was a handsome kid; he had eyes that were large and dark and always seemed to shine with tears, a straight nose, a clear complexion... In the soft light radiating from the Gaskell's house he looked painfully young. "I crashed. I came with Hannah Green."

"That's all right," I said. Hannah Green was the most brilliant writer in the department. She was twenty years old, very pretty, and had already published two stories in The Paris Review. Her style was plain and poetic as rain on a daisy--she was particularly gifted at the description of empty land and horses. She lived in the basement of my house for a hundred dollars a month, and I was desperately in love with her. "You can say I invited you. I ought to have, anyway."

...

"Are you and Hannah seeing each other?" I said after a moment. Lately, I knew, they had been palling around together, going to movies at the Playhouse and Filmmakers'. "Dating?"

"No!" he said immediately. It was too dim to see if he blushed, but he looked down at his feet. "We just came from Son of Fury at the Playhouse." He looked up again and his face grew more animated, as it generally did when he got himself onto his favorite subject. "With Tyrone Power and Frances Farmer."

"I haven't seen it."

"I think Hannah looks like Frances Farmer. That's why I wanted her to see it."

"She went crazy, Frances Farmer."

"Sod did Gene Tierney. She's in it, too."

"Sounds like a good one."

"It's not bad." He smiled. He had a big-toothed crooked smile that made him look even younger. "I kind of needed a little cheering up, I guess."

"I'll bet," I said. "They were hard on you today."

He shrugged, and looked away again. That afternoon, as we had gone around the room, there was only one member of the workshop with anything good to say about James's story: Hannah Green, and even her critique had been chiefly constructed out of equal parts equivocation and tact. Insofar as the outlines of its plot could be made out amid the sentence fragments and tics of punctuation that characterized James leer's writing, the story concerned a boy who had been molested by a priest and then, when he began to show signs of emotional distress through odd and destructive behavior, was taken by his mothers to the same priest to confess his sins. The story ended with the boy watching through the grate of the confessional as his mother walked out of the church into the sunshine, and with the words "Shaft. Of light."

Pg. 51:

"Dr. Gaskell collects them. He has a lot of memora-- oh." The air before my eyes was suddenly filled with spangles, and I felt my knees knock against each other. Reaching out to steady myself, I took hold of James's arm. It felt weightless and slender as a cardboard tube.

"Professor? Are you all right?"

"I'm fine, James. I'm just a little stoned."

"You didn't look so well in class today. Hannah didn't think so, either."

"I haven't been sleeping well, myself," I said. As a matter of fact I had, during the last month, been experiencing spells of dizziness and bewilderment that came over me suddenly... "I'll be fine. I'd better get my old fat body inside."

Pg. 52:

Just before James started around the corner he looked up, at the back windows of the house, and stopped dead, his face raised to catch the light spilling out from the party. He was looking at Hannah Green, who stood by the dining-room window with her back toward us. Her yellow hair was mussed and scattered in all directions. She was telling a story with her hands. All the people standing in front of her had bared their teeth to laugh.

Pg. 53-55:

"Grady," said one of the students, a young woman named Carrie McWhirty... "Hannah was looking for you. Hi, James."

"Hello," said James, glumly.

"Hannah?" I said. At the thought that she had been looking for me my heart was seized with panic or delight. "Where'd she go?"

"I'm out here, Grady," called Hannah from the foyer. She stuck her head into the living room. "I was wondering what happened to you guys."

"Uh, we were outside," I said. "We had a few things to discuss."

"I don't doubt it," said Hannah, reading the pink calligraphy inked across the whites of my eyes. She had on a man's plaid flannel shirt, tucked imperfectly into a baggy pair of Levi's, and the cracked red cowboy boots I'd never once seen her go without, not even when she prowled the house in a terry-cloth bathrobe, or a pair of sweatpants, or running shorts. In idle moments I liked to summon up an image of her naked feed, long and intelligent, aglitter with down, toenails pained red as the leather of her boots. Beyond the mess of her dirty blond hair, however, and a certain heaviness of jaw--she was originally from Provo, Utah, and she had the wide, stubborn face of a Western girl--it was difficult to see much of a resemblance to Frances Farmer; buy Hannah Green was very beautiful, and she knew it all too well, and she tried with all her might, I thought, not to let it [EXPLETIVE] her up; maybe it was in this doomed struggle that James Leer saw a sad resemblance. "No, but really," she said. "James, do you need a ride? I'm leaving right now. I was planning to give your friends a ride, too, Grady. Terry and his friend. Who is she, anyw-- hey. Grady, what's the matter? You look kind of wiped."

She reached out to put a hand on my arm--she was a person who liked to touch you--and I took a step away from her. I was always backing off from Hannah Green, pressing myself against the wall when we passed each other in a wide and empty hallway, hiding behind my newspaper when we found ourselves in the kitchen alone, with an admirable and highly unlikely steadfastness that I had a hard time explaining to myself. I suppose that I derived some kind of comfort from the fact that my relationship with young Hannah Green remained a disaster waiting to happen and not, as would normally have been the case by this time, the usual disaster.

"I'm just fine," I said. "I think I'm coming down with something. Where are those two?"

"Upstairs. They went to get their coats."

"Great." I started to call up to them, but then I remembered James Leer... "Heh, uh, Hannah, could you take them for me, and I'll drive James? We're not, uh, we're not quite through here."

"Sure," said Hannah. "Only your friends went up there two get their coats, like, ten minutes ago."

Pg. 56-58:

"Oh, listen, Terry," said Hannah Green, tugging at Crabtree's elbow as if she had known him all her life. "This is the guy I was telling you about. James Leer. Ask him about George Sanders. James will know."

"Ask me what?" said James, freeing his pale hand at last from Crabtree's grip... "He was in Son of Fury."

"Terry was saying how George Sanders killed himself, James, but he didn't remember how. I told him you'd know."

"Pills," said James Leer. "In 1972."

"Very good! The date, too!" Crabtree handed Miss Sloviak her coat. "Here," she said.

"Oh, James is amazing," said Hannah. "Aren't you, James? No really, watch this, watch this." She turned to James Leer, looking up at him as though she were his adoring little sister and thought him capable of limitless acts of magic. You could see the desire to please her freezing up all the muscles of his face. "James, who else committed suicide? What other movie actors, I mean?"

"All of them? There are way too many."

"Well, then, just a few of the big ones, let's say."

He didn't even roll back his eyes in his head, or scratch reminiscently at his chin. He just opened his mouth and started counting them off on his fingers.

"Pier Angeli, 1971 or '72, also pills. Charles Boyer, 1978, pills again. Charles Butterworth, 1946, I think. In a car..." [James recounts numerous Hollywood actors who committed suicide.]

"I haven't heard of half of those," said Hannah.

"You did them alphabetically," said Crabtree.

James shrugged. "That's just kind of how my brain works," he said.

"I don't think so," said Hannah. "I think your brain works a lot more weirdly than that. Come on. We have to go."

...[Miss Sloviak] refused to let Crabtree take her arm and instead made a point of taking hold of Hannah Green, who said, "What's that you're wearing? It smells so familiar."

Pg. 65-66:

"My wife left me today," I said, as much to myself as to James Leer.

"I know," said James Leer. "Hannah told me."

"Hannah knows?" Now it was my turn to cover my face with my hands. "I guess she must have seen the note."

"I guess so," said James. "It seemed like she was kind of happy about it, to tell you the truth."

"She what?"

"Not--I mean, Hannah said a couple of things that, well. I never got the impression, you know, that she and your wife actually liked each other. Very much. I mean, actually it sounded to me like your wife kind of hated Hannah."

"I guess she did," I said, remembering the creaking silence that had reached like the arm of a glacier across my marriage, in the days after I'd invited Hannah to rent our basement. "I guess I don't really know a whole lot about what's going on in my own house."

"That could be," said James, a certain wryness entering his tone. "Did you know that Hannah Green has a crush on you?"

"I didn't know that," I said, falling backward on the bed. It felt so good to lie back and close my eyes that I was afraid to stay that way. I sat up, too quickly, so that a starry cloud of diamonds condensed around my head. I didn't know what to say next. I'm glad? So much the worse for her?

"I think so, anyway," said James. "Hey, you know who else I forgot? She only made one movie, Thirteen Women, 1932..."

Pg. 77:

I was drunk on five swallows of Jack Daniel's and a heavy dose of oxygen from our run across the campus, and all the radiant things around me, the stage lights, the gilt wall sconces, the back of Hannah Green's golden head seven rows away from me, the massive crystal chandelier suspended above the audience... and most of all I was not thinking about Wonder Boys. I watched Hannah Green nod her head, tuck a strand of hair behind her right ear, and in a gesture I knew well, raise her knee to her forehead and slip her hands down into her boot to give a sharp upward tug on her sock. I passed ten blissful minutes without a thought in my head.

Pg. 78:

[James Leer] covered his mouth, ducked his head, and looked up at me, his face as red as Hannah Green's boots. I shrugged. All the people who had turned to look at James now returned their gazes to the podium; all except one. Terry Crabtree was sitting three seats away from Hannah, with Miss Sloviak and Walter Gaskell between them...

Pg. 101:

Out on the [dance] floor [of the Hi-Hat club/restaurant] there were a handful of couples doing the buckethead and the barracuda and the cold Samoan, to the weary and inexorable groove of "Baby What You Want Me to Do," and near the center of the crowd of dancers were Hannah Green and Q., the man who haunted his own life. Hannah was an ungraceful but energetic dancer, capable of admirable feats of pelvic abandon, but the best you could say for old Q. was that he was making no effort to cling to some outmoded notion of dignity. It sounds uncharitable of me to say so, I know, but his attention seemed to be occupied less by his own movements than by the slow vertical mambo of Hannah Green's breasts. I waved to Hannah, who smiled to me, and when I looked around and gave my shoulders an exaggerated shrug, she pointed to a table in a far corner, away from the dancers, the bandstand, and all the other customers.

Pg. 102:

I shot what must've been a fairly panicked look at Hannah, who bared her teeth and screwed up her eyes, the way you do when an ambulance goes screaming by.

Pg. 104-105:

"I like the way she dances," said Crabtree, looking out across the floor toward Hannah Green and Q. The selection now playing was "Ride Your Pony," by Lee Dorsey.

Pg. 107:

"Hey, teach," said Hannah Green, bounding toward us in her sharp red boots. "I want you to come and dance with me."

We danced, to "Shake a Tail Feather," and "Sex Machine," and some scratchy Joe Tex number whose title I couldn't recall. I danced with Hannah until the band came off break, and as they climbed up onto the platform and got behind their various instruments I went back over to the table...

Pg. 108-111:

Then I went back out onto the floor and danced for another hour to what grizzled old Carl Franklin called the R & B stylings of Pittsburgh's very own Double Down, until I could no longer feel my ankle and had lost the better part of my shame. Hannah rolled up her sleeves, and unbuttoned the top two buttons of her flannel shirt, revealing the threadbare neckline of a white ribbed undershirt and a filigreed locket on a thin silver chain.

While she danced she kept her eyes closed and described solitary, interlocking circles across the floor, so that there were moments when I felt that she wasn't really dancing with me at all, but simply employing me as a kind of fulcrum, a hub on which to hang the whirling spokes of her own private revolutions. And no wonder, I thought; if I were her I certainly wouldn't have wanted anyone to think that I could possibly have chosen such an elephantine piece of machinery as myself, all vacuum tubes and gear work with a plain old analog dial of a face, such a dented, gas-guzzling old Galaxie 500 of a man, for a dance partner. But then she would open her eyes, favor me with her spacious Utah smile, and give me her hands, so that I could spin her for a second or two. Whenever our faces drew within each other's orbit I felt compelled to speak, generally to express my doubts about the wisdom of my dancing, with her, at all, and when Double Down broke their set again I was relieved, and I started for the table. But she took hold of my wrist, dragged me over to the magic black telephone, and dialed up three songs.

"'Just My Imagination,'" she told the operator, without consulting the tattered playlist, "'When a Man Loves a Woman.' That's right. And 'Get It While You Can.'"

"Uh oh," I said. "I'm in trouble."

"Hush now," said Hannah, as she reached up and put her arms around my neck.

"I'm going to regret this tomorrow," I said.

"That's nice," she said. "Everybody ought to have a hobby."

A few other couples joined us on the dance floor and we lost ourselves among them... I forgot, for a moment, all the bad things that had already happened to me that day as a result of my foolishness and bad behavior, and all the good reasons I had for leaving poor Hannah Green alone. I was happy. I kissed Hannah's apple yellow hair...

"I've been rereading Arsonist," she told me, to cheer me up, I supposed. "It's so great." She was referring to my second novel, The Arsonist's Girl, an unpleasant little story of love and madness I'd written during the Final Days, down inside the doomed bunker of my second marriage to a San Francisco weatherwoman whom I'll just call Eva B. It was a slender book, whose composition had cost me a lot misery, and I had a pretty low opinion of it, myself, although it did contain a nice description of a fire at a petting zoo... "It's so [EXPLETIVE] tragic, and beautiful, Grady. I love the way you write. It's so natural. It's so plain. I was thinking it's like all your sentences seem as if they've always existed, waiting around up there, in Style Heaven, or wherever, for you to fetch them down."

"I thank you," I said.

"And I love what you wrote in your inscription, Grady."

"I'm glad."

"Only I'm not quite the downy innocent you think I am."

"I hope that isn't true," I said, and at that moment I happened to catch a glimpse, in the smoky mirrored wall of the Hi-Hat, of an overweight, hobbled, bespectacled, aging, lank-haired, stoop-shouldered Sasquatch, his furry eye sockets dim, his gait unsteady, his arms enfolded so tightly around the bones of a helpless young angel that it was impossible to say if she was holding him up or if, on the contrary, he was dragging her down. I stopped dancing and let go of Hannah Green, and then Janis Joplin ceased urging us not to turn our backs on love, and the last of Hannah's requests came to an end. In its aftermath we stood there, suddenly abandoned by the other couples, looking at each other, and all at once, as the pills and whiskey fell out of balance in my bloodstream, I felt irremediably [EXPLETIVE] up.

"So what are you going to do?" said Hannah, giving my belly a friendly slap.

My reply was something softheaded and mumbled about dancing with her all night.

"About Emily, I mean," she said, a little impatiently. "I--I guess she isn't going to be there when you get home."

"I guess not," I said. "Try not to look quite so pleased."

She blushed. "Sorry."

"I guess I really don't know. What I'm going to do."

"I have an idea," she said. She fished around in the pocket of her jeans for a moment, and then pressed three warm quarters into my palm.

I steered myself over to the telephone, dropped in the quarters, and unhooked the receiver [of the jukebox phone]...

Pg. 112-114:

I looked over at Hannah and tried to flash her the smile of a competent and reasonable smiler, of someone who wasn't at all worried that he was going to be sick, and going to fall down, and going to hurt yet another young woman in the course of a lifelong career of callous disregard. Judging from the looking of dismay that came over her face, I thought I must have failed miserably, but then I saw that Q. had left the table and was making his way across the crowded room toward Hannah, his face grim and determined and haunted, as far as I could see, only by alcohol, the writer's true secret sharer... As he approached, however, to ask her for the next dance, Hannah turned on him, simply, and headed straight toward me, head lowered, blushing from her forehead to the nape of her neck at the thought of her own rudeness.

"Just a minute," I told the Jukebox Crone, wrapping my hand around the mouthpiece of the receiver. "Dance with him, Hannah." I tried out another of my implausible smiles. "He's a famous writer."...

"But I don't want to dance with him, Grady." Hannah put her arm through mine and looked up at me through her scattered bangs, searching my face, her eyes so wide and desperate that I was alarmed. I'd never seen Hannah acting anything other than the calm, optimistic Mormon girl she was, eternally polite, capable of stolid acceptance of locusts, misfortune, and outlandish news about the universe. "I want to keep dancing with you."

"Please." I watched as Q. turned and walked with drunken precision back to the table in the far corner of the room...

I hung up the phone, gave Hannah a sloppy inarticulate hug, and apologized to her about forty-seven times, until neither of us knew what I was talking about and she said that it was all right. Then I hurried over to the table in the corner, where I laid my cold fingers against James Leer's feverish neck.

"In ten seconds," I told them, as I helped James to his feet, "this dance floor is going to be packed."

Hannah said that she had never been there but she believed James Leer rented a room from his Aunt Rachel, in the attic of her house in Mt. Lebanon. Since neither of us felt like driving all the way out to the South Hills at two o'clock in the morning, I folded James into Hannah's beat-to-sh-- Le Car and sent them on home to my house. Crabtree and Q. would be riding with me. I figured it would be safer that way for all of us.

As I was about to close the door on him, James stirred and wrinkled up his face.

"He's having a bad dream," I said.

We watched him for a moment.

"I'll bet James's bad dreams are really bad," said Hannah. "The way bad movies are... His bag," said Hannah. "You know that ratty green thing of his?"

Pg. 116-118:

Then I rolled on out of the Hat. My car and Hannah's were idling side by side at the center of the nearly empty parking lot... I walked over to Hannah's car and knocked on her window, and then the air around me was filled, an inch at a time, with the radiance of her face and with the wheezing of a tragic accordion. Hannah Green was big on tango music.

"No knacksap," I said. "He must have left it back at Thaw."

"Are you sure?" she said. "Maybe someone took it."

"No. Nobody took it."

I shrugged, and bent down to look at James. He'd slumped over against Hannah, now, and his head rested on her shoulders with an enviable smugness.

"Is he all right?" I said.

"I think so." She gave the hair over his ear a few unconscious strokes. "I'm just going to get him home and onto the sofa." She ducked her head and looked at me pleadingly. "The one in your office, all right?"

"In my office?"

"Yeah, you know it's the best one for naps, Grady." Over the course of the previous winter, as I read student writing or caught up on correspondence at my desk, Hannah had dozed off many times while studying on my old Sears Honor Bilt, her bootheels kicked up on the creaking armrest, her face sheltered under the tent of a sociology text.

"I don't think it's really going to make all that much difference to him right now, Hannah," I said. "We could probably stand him up out in the garage with the snow shovels."

"Grady."

"All right. In my office." I hung a couple of fingers over the edge of her window, and she reached up and took them in her own.

"See you at home," I said.

Pg. 129-130:

I could see it was, because the lamp on my desk was still on. I supposed that Hannah had left it burning for James in case he awakened in the middle of the night and didn't know where he was.

Pg. 130-131:

When I woke on Saturday morning... I lay for a moment, riding the swell and roll of my hangover... I'd already lost most of the details, but I could still recall its backdrop or central theme, which was the shadowy kingdom of mystery and spice hidden in the parting of Hannah Green's thighs.

[Grady catches Hannah Green reading his unfinished manuscript:]

Pg. 256-260:

There was only one writer in my office. She was sitting alone on the Honor Bilt, with the door closed, her knees pulled up under her sweater so that the pointy tips of her boots peeked out from under the hem. Her head was bowed, and she was concentrating on a thick manuscript stacked on the sofa beside her, twisting a long yellow strand of hair around one finger and then untwisting it again.

"Hey," I said, coming into the room, closing the door behind me. I looked over at my desk. It was only then I realized that I'd left the house that morning with Wonder Boys lying out in the open where anyone--where Crabtree--could get at it.

"Oh!" said Hannah, slapping back onto the stack the page she'd been about to set to one side, covering it with both hands, as though it were something she herself had written and didn't want me to see. "Grady! Oh, God, I'm so embarrassed. I hope you don't mind. It was just sort of lying out." She wrinkled up her nose at the thought of her own misbehavior. "I suck."

"You suck not," I said. "I don't mind at all."

She reassembled the scattered slices of the Grady's Wheel of Cheese, upended it, carefully tapped it against the sofa cushion, and set the thing down on an arm of the sofa. Then she got up and came over to get her arms around me.

"I'm so glad to see you," she said. "We tried to find you everywhere. We were worried."

"I'm fine," I said. "I just had to deal with a little outbreak of Cetusian fever."

"How's that?"

"Nothing." I nodded toward the manuscript balanced on the edge of the sofa. "Did, uh, did Crabtree happen to see any of that, do you know?"

"No, I don't know," said Hannah. "I mean, I wouldn't think so. We were gone all day, over at WordFest. We didn't get back until late." She grinned. "And he was pretty busy after that."

"I'll bet he was... So, listen, where is the old Crab, anyway?"

"Who knows? I've been in here for a couple of hours. I don't even know if he's here or--oh, no, don't go!" She redoubled her hold on me. "Stay, where are you going?"

"I really need to talk to him," I said, though all of a sudden the prospects of getting into my car.... struck me as less than appealing. I could just stay here with Hannah, and forget all about Deborah and Emily, and Sara... and above all that the poor lost liar Jimmy Leer. She was holding me and I closed my eyes and in my mind I followed her downstairs to her apartment, and lay beside her on her sateen comforter, under the Stieglitz portrait of Georgia O'Keeffe, and plunged my hand down into the mouth of her cowgirl boots, and ran my fingers along the damp slender arches of her feet. "I really need--"

"The Horse" came on, out in the living room, and Hannah grabbed hold of my hand.

"Come on," she said. "You need to dance."

"I can't. My ankles."

"Your ankles? Come one."

"I can't." She got me to the door and pulled it open, letting in a bright blast of horn charts. She rocked her skinny cowgirl hips a couple of times around. "Look, Hannah, James got himself--he got himself into a little bit of trouble tonight. I need Crabtree to help me go get him out."

"What kind of trouble? Let me come."

"No, I can't say, it's nothing. Look, he and I'll go get James, okay, it won't take long, we'll bring him back, and then I'll dance with you. All right? I promise?"

"He shot the Chancellor's dog, didn't he?"

"He did?" I said, pushing the door closed again. "Shot what?"

"Somebody shot their dog last night. The blind one. That's what the police think, anyway. The dog's missing, and they found some spots of blood on the carpet. And then I heard Dr. Gaskell dug a bullet out of the door."

"Jesus," I said, "That's terrible."

"Crabtree thought that it sounded like something James would do."

"He doesn't even know James," I said.

"Who does?" said Hannah.

You don't, I thought. I gave her hand a squeeze.

"I'll be right back," I told her.

"Can't I come with you?"

"I don't think you should."

"I know savate."

"Hannah."

"Oh, all right," she said. Back home in Provo, Hannah had nine older brothers, and she was accustomed to the abandonment of boys. "Can I at least keep reading Wonder Boys until you come back?"

It hadn't really sunk in until now that someone had actually been reading my book. It was a painful and exhilarating thought.

"I guess so," I said. "Sure."

Hannah poked a finger between my belly and my belt buckle and tugged until I nearly fell against her.

"Can I take it down into my room and be alone with it?"

"I don't know," I said, taking a step backward. I was always, I thought, taking a step away from Hannah Green. "How are you liking it?"

"I think I'm loving it."

"Really?" I said. Hannah's praise, though lightly given, struck me with unexpected force, and I felt my throat construct. I saw how lonely a pursuit the writing of Wonder Boys had become, how sequestered and directionless and blind. I'd shown some early chapters to Emily, and her only memorable comment at the time had been "It seems awfully male." I'd laughed this off, but ever since then I'd been the book's only reader, the prophet, founder, and sole inhabitant of my own failed little Pennsylvania utopia. "All right, then. Sure you can."

"I kind of think I'm loving you," she said. "Too."

Oh, what the hell, I thought. Maybe I'd better just stay.

"Tripp's here?" said Crabtree from somewhere out in the hall. His voice sounded plaintive and so relieved that I felt a pang of guilt at the sound of it. "Where is he? Tripp?"

I started, and pulled away from her.

"Don't let him see that thing, okay?" I said. "Hide it till we leave." I gave her a peck on the cheek and stepped out onto the hall. "I'll see you soon."

"Be careful," she said, brushing at a strand of hair that had gotten caught in the lip balm at the corner of her mouth.

"I will," I said.

As long as she was falling in love with me, I might as well start making her promises I didn't intend to keep.

Pg. 286:

I went down to Hannah's room. All the lights were on, and she was lying on her bed, surrounded by the scattered pages of Wonder Boys, asleep. She was dressed in a white nightgown, lace at the bodice. Her feet were bare. They were thick, wide, ordinary feet, with long crooked toes. I sat down on the edge of her bed and hung my head. From this vantage I could see the little moth lying in my pocket. I fished him out and stared at him for a while.

"What are you holding in your hand?" said Hannah.

I started. She was looking at me through half-closed lids, not really awake. I uncurled my fingers, revealing the moth, embalmed in a thin white coating of wax.

"Just a moth," I said.

"I fell asleep," she told me, her voice cobwebbed with sleep. "I was reading."

"That good, huh?" I said. There was no reply. "How far did you get?"

But her eyes had fluttered again. I looked at the clock. It was four thirty-two in the morning. I collected the parts of my manuscript, slapped them together, and set them on the nightstand beside her bed. Her bedclothes were all knotted and twisted, so I shook them out and let them fall billowing over her like parachute silks. I covered her feet, kissed her cheek, and wished her good night. Then I turned out the lights and went back upstairs to my office.

Pg. 298:

The front door was open, and deep in the house I heard the melancholy wheezing of an accordion. Hannah was awake and making breakfast; there was a clamor of pots from the kitchen. I was suddenly afraid of having to face her, and I wondered at this; and then in the next instant I realized that what I feared was not Hannah but her opinion of Wonder Boys. I felt intimations of disaster there; my book was at last going forth into the world, not, as I'd always imagined, like a great black streamlined locomotive, fittings aglint, trailing tricolored bunting, its steel wheels throwing sparks; but rather by accident, and at the wrong time, a half-ton pickup with no brakes, abruptly jarred loose from its blocks in the garage and rolling backward down a long steep hill.

Pg. 299-303:

Hannah Green and the inevitable Jeff were cracking eggs into a crockery bowl and peeling strips of bacon from the package. Heartbroken Argentine music came blowing up the stairs from the basement, and as we walked into the kitchen we found Jeff lecturing a skeptical Hannah on the origins of the tango in the death grip and knife play of latent homosexual love, an argument which I recognized as cribbed from old George Borges. Maybe, I thought, this Jeff character had something to recommend him; there was a certain thematic aptness, after all, in trying to make a girl through the plagiarism of Borges...

"Get out of here," said Hannah, picking large fragments of eggshell out of the bowl.

"I'm serious."

"Jeff," said Crabtree, shaking his head sadly. "Jeff, we have to have a talk."

"Oh, hi!" said Hannah, looking up. She gave me an awkward, oddly formal wave. She had on a long purple nightshirt over her cracked red boots. Her index finger wore a smart eggshell hat. Her eyes were bright, her cheeks pink, and when she spoke she sounded well-rested and strong and a bit over-eager, like someone whose fever has just broken. "You fellas want some eggs?"

"I shook my head and then pointed toward the basement door.

"Can I talk to you a sec, Hannah?" I said...

"What's up?" said Hannah, looking concerned.

I told her that James had been taken away by the police, and that rescuing him would be a simple thing, but that in order to rescue him we would need to borrow her car. The sudden disappearance of my own vehicle I explained with a vague but suitably ominous allusion to Harry Blackmore. No, I said, shaking my head in the same vague and ominous but supremely self-possessed manner, it would be better if she herself didn't come along. She and Jeff should just head on over to WordFest, and in an hour--easy--James, Crabtree and I would be joining them. That was all I told her--it was all I thought I needed to tell her--but to my surprise she did not immediately agree to let us take her car. She hugged herself, stepped backward toward her bed, and sat heavily down. The manuscript of Wonder Boys stood in a stack on her night table, spotless, smooth-edged, all its corners true. Hannah regarded it for several seconds, then turned her face to me. She was biting her lower lip.

"Grady," she said. She took a deep breath, then slowly let it out. "Are you at all stoned, by any chance."

I was not, and I swore to her that I was not. The claim sounded completely false to my ears. I could see she didn't believe me, and, in the way of things, the more I promised her, the falser I sounded.

"Okay, okay, ease up," she said. "It's not really any of my business. I wouldn't even--I mean, normally--"

"I was surprised at how upset she seemed. "What, Hannah? What is it?"

"Sometimes I think you smoke too much of that stuff."

"Maybe I do," I said. "Yeah, I do. Why? I mean, what makes you say so?"

"It's not-- I didn't want to--" She reached for Wonder Boys. Its weight bent her hand at the wrist, and when she dropped it onto her lap it resounded against her knee bones like a watermelon. She looked down at its first page, at the initial run of sentences I'd written and rewritten two hundred times. She shook her head and started to speak, then closed her mouth again.

"Just say it, Hannah. Come on."

"It starts out great, Grady. Really great. For the first two hundred pages or so I was loving it. I mean, you heard me last night."

"I heard you," I said, my heart squeezing itself into a tight fist of dread.

"But then--I don't know."

"Don't know what?"

"Well, then it starts--I mean parts of it are still wonderful, amazing, but after a while it just starts--I don't know--it gets all spread out."

"Spread out?"

"Okay, not spread out, then, but jammed too full. Like that thing with the Indian ruin? Okay, first you have the Indians come, right, they build the thing, they die out, it falls apart, hundreds of years go by, it gets buried, in the fifties some scientist finds it and digs it out, he kills himself--all that goes on and on and on, for, like forty pages, and, I don't know--" She paused, and blinked her eyes, and wondered for a moment at the novelty of administering criticism to her teacher. "It doesn't really have anything to do with your characters. I mean, it's beautiful writing, amazingly beautiful, but . . . And all that about the town cemetary? All the headstones, and their inscriptions, and the bones and bodies underneath them? And the pat about their different guns in the cabinet in the old house? And the genealogies of their horses? And--" She caught herself devolving into simple litany and broke off.

"Grady," she said, sounding more than a little horror-struck. "You have whole chapters that go on for thirty and forty pages with no characters at all!"

"I know." I knew, but it had never quite occurred to me to put it to myself this way. There were, I was suddenly certain, a lot of things about Wonder Boys that had never occurred to me. On a certain crucial level--how strange!--I had no idea of what the book was really about, and not the faintest notion of how it would strike a reader. I hung my head. "Jesus."

"I'm sorry, Grady, really, I just couldn't help wondering--"

"What?"

"I wondered how it would be--what this book would be like--if you didn't--if you weren't always so stoned all the time when you write."

I pretended to be indignant. "It wouldn't read half as well," I said, sounding more dishonest to myself than ever. "I'm certain of that."

Hannah nodded, but she didn't meet my eyes, and the tips of her ears turned red. She was embarrassed for me.

"Wait till you finish it," I said. "You'll see."

Again she didn't reply, but now she managed to bring herself to look at me, and her face was the face of a woman who, having at the last moment discovered that all of her fiance's claims and bonafides were false, all of his credentials forged, has unpacked her trunks and cashed in her ticket and now must tell him quickly that she will not sail away. There was pity there, and resentment, and a Daughter-of-Utah hardness that said, Enough's enough. However far she'd gotten in her reading last night and this morning, the thought of pressing onward to the end was obviously too onerous for her even to contemplate.

"Anyway," I said, glancing away. I cleared my throat. It was my turn to be embarrassed. "Is it all right about the car?"

"Of course," she said, with cruel charity and a backward wave of her hand. "Keys are on the dresser."

"Thanks."

"No problem. You guys take good care of James, now."

"We will." I turned away. "You betcha."

"Grady," she said.

I looked back, and she held out the manuscript to me as though returning a ring. I took it, grabbed the keys, and started back up the stairs.

Pg. 328:

I switched over to AM and spun the radio dial until I hit polka music. I opened and closed my window a few times, fiddled with the rearview mirror, adjusted my seat, opened and closed the glove compartment. Hannah kept hers very neat, and well stocked with the road maps that had gotten her from Provo to Pittsburgh two years before. There was a flashlight, and a small box of tampons, and a flat tin of Wintermans little cigars. This, I thought, looked vaguely familiar.

I snapped it open and found that it contained, of all things, a sheaf of tight little marijuana cigarettes, expertly rolled. I wasn't at all surprised by their precision because I had rolled them myself, and given the box to Hannah on her birthday last October. At the time I'd rolled her a dozen; there were still twelve in the can.

Pg. 339:

"Were you looking for Hannah?" She pointed. "She's over there."

I knew that I shouldn't have, but--so--I looked. Hannah was sitting several rows from the stage, off to the right-hand side of the orchestra, on the aisle. She was nodding her head, every so often, and smirking into her cupped hand., and I could see that the person on the other side of her was entertaining her more than Walter Gaskell--doubtless at the latter's expense. Her hair was pulled back in a clip, exposing her neck. A hand appeared around the back of her head and settled lightly on her left shoulder, and she suffered it. She kicked her long legs in their bright red boots. THe printed program slid from her lap, and when she leaned down to retrieve it I saw beside her a cheerful pink face framed in long hair even fairer than hers. I saw back and closed my eyes.

"Who is that guy?" said Carrie. "Do you know him?"

"His name's Jeff," I said.

Pg. 41:

"Take a bow, James," called Hannah Green, loud enough for everyone in the auditorium to hear. There was laughter. James looked at her. He had gone bright red in the face... he... took his first sweet bow as a wonder boy.