From: Susan Sackett, The Hollywood Reporter Book of Box Office Hits, Billboard Publications: New York City (1990), page 98:

THIS IS CINERAMA

CINERAMA RELEASING CORPORATION (CRC)

$15,400,000 [theatrical rentals, or approximately $33,572,000 in U.S. gross ticket sales. This was the #1 highest grossing film of the year, according to Sackett's book.]

"Ladies and gentlemen, this is CINERAMA!"

-- Lowell Thomas

It starts with a basic 35-millimeter screen. Lowell Thomas, famed world traveler, narrates a very long black-and-white documentary on the history of art, from early cave paintings through 19th-century attempts at motion pictures. We are given the impression that all that has gone before had but one goal to attain--the miraculous achievement Thomas has been leading up to for ten tedious minutes--Cinerama! With a sudden smash cut to full color, the screen suddenly widens to three times its previous size as we enter a roller coaster, go up the ramp, then find ourselves hurtling at breakneck speed back down to a chorus of screams from the unseen patrons (we're in the front car) in the most memorable and famous point-of-view shot of all time.

Ask anyone what they know or remember about Cinerama and they will inevitably tell you, "The roller coaster ride." This sequence would be considered tame today by a generation raised on the great special effects of films like Star Wars, but seen as a museum piece, it is easy to understand why people were so enthralled.

To begin with, it was a big screen, a very big screen--certainly bigger than the tiny TVs in people's living rooms. It was not the first time wide-screen had been attempted, however. Back in 1896, an Englishman named Birt Acres shot a local regatta in 70-millimeter, but he soon abandoned the use of wide-gauge film as too costly. In 1929, Fox Movietone Follies became the first wide-screen 70-millimeter feature film shown in New York, but it was a curiosity, not ready for mass distribution.

Cinerama was developed by Frederick Waller of Huntington, New York. His original idea was to use 1116-millimeter projectors to cover a vast area of screen. There were numerous technical problems at first, but eventually he was successful.

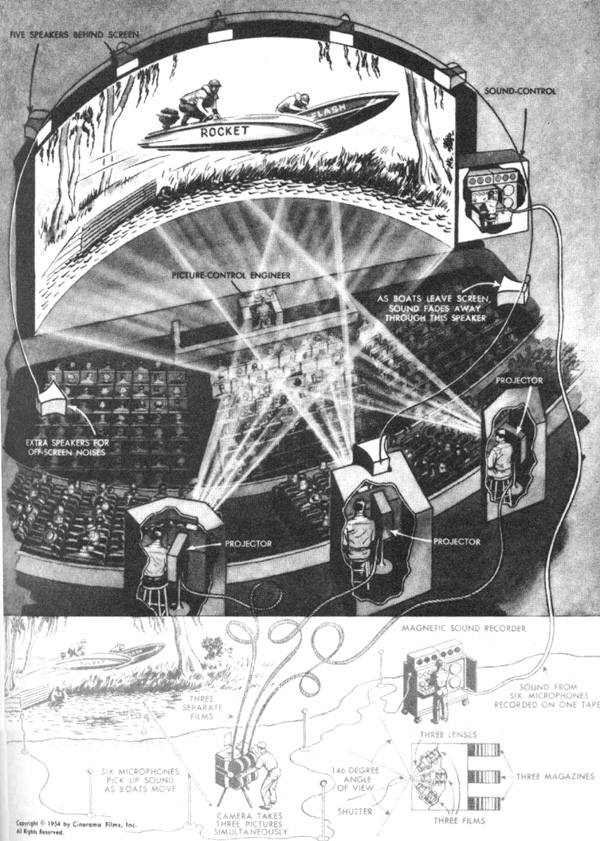

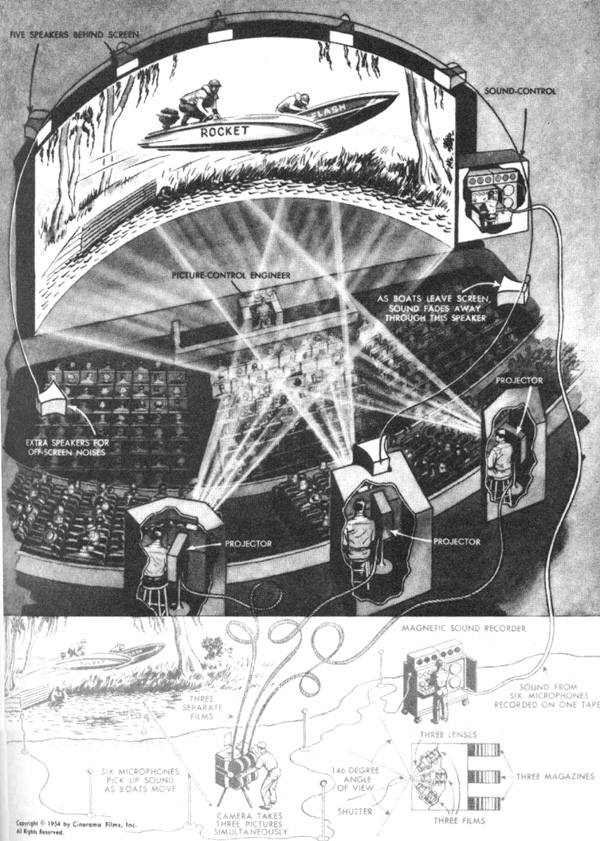

Through three separate 27-millimeter lenses--each of which roughly

resembled the lens of a human eye--the Cinerama cameras took three pictures simultaneously on three separate rolls of film. Set at 48-degree angles to each other, each lens covered precisely one-third of the entire picture--the one on the right photographing the left third, the one on the left photographing the right third, and the one in the center shooting straight ahead. A single rotating shutter assured simultaneous exposures on each of the films, while single focus and diaphragm controls adjusted the settings on all three lenses at the same time. The footage was then shown in the theater by three projectors, producing a wider-than-average image. These projectors, grounded in concrete, were locked together by motors that automatically kept the three images in perfect synchronization on the screen. Tiny comblike bits of steel were fitted into each projector at the side of the film gate. Jiggling up and down along the edges of the film at high speed, they fuzzed the edges of the pictures to minimize the lines between them. Oversized reels which fed film to the Cinerama projectors held 7,500 feet (50 minutes' worth) of film. It was a cumbersome process at best, by today's standards, but the novelty was just what was needed to compete with television.

Audiences ate it up. Tickets were on a reservations-only basis, often sold out weeks in advance. This Is Cinerama ran more than two years in New York alone, and played in limited engagements around the country. Only 47 theaters in the world were able to show Cinerama, with its 97-foot-wide screen and special equipment. Had even more theaters been able to make the equipment conversion, the film undoubtedly would have made even more millions.

The medium was definitely the message. There was absolutely no story in This Is Cinerama. In addition to the roller coaster, the audience watched a ballet, a helicopter ride over Niagara Falls, and a church organ service (with a locked-off camera, making for one of the dullest segments ever put on film -- audiences, however, were enchanted). A gondola ride in Venice, bagpipes in Scotland, the Vienna Boy's Choir, and a bullfight in Spain, plus a ho-hum segment at Florida's Cypress Gardens, were all on the program. There were two excellent numbers. The first was a visit to La Scala Opera House in Italy, where we witnessed a spectacular performance of Aida with what seemed like half of Italy in the chorus. The second was the film's final segment, which featured a stirring flyover of the United States, including forests, wheatfields, the Golden Gate, and the Grand Canyon, all set to the music of the Mormon Tabernacle Choir.

This is the sort of film that will never be seen again by most people, since it is not suitable for release on videocassette. In 1988, there was a reissue of This Is Cinerama at Los Angeles' Cinerama Dome--a theater which claims to have never actually shown a film in Cinerama, and normally runs only modern blockbuster films like E.T. and Who Framed Roger Rabbit. Most of the people in the audience were either film students or older couples, there to recaptue some of the thrill they felt when Lowell Thomas first said those magic words.

Developed by Fred Waller

Stereophonic sound concept by Hazard Reeves

Produced by Merian C. Cooper and Robert L, Bendick

Narrated by Lowell Thomas

ACADEMY AWARD NOMINATIONS:

1 nomination, no wins

Best Scoring of a Dramatic or Comedy Picture

Producer Merian C. Cooper received an honorary statuette "for his many innovations and contributions to the art of motion pictures."

Fred Waller was presented with a special Oscar "for designing and developing the multiple photographic and projection systems which culminated in Cinerama."

BELOW: Illustration from the This Is Cinerama program booklet shows how Fred Willer's three-camera, three-projector process works.